My Way or the High Way? Why every teacher needs to be different

|

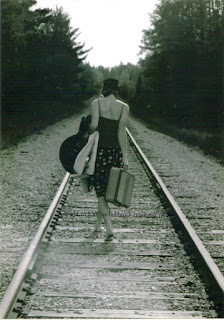

| One road? |

What if I wanted to change a fuse on the Mir Space Station. Could I use the same screwdriver? I imagine not; I fancy that NASA have designed something with a torch and a magnetic strap. The concept of using different tools for different situations is not, I hope, a controversial one, although anything's possible on Twitter, I suppose (WHY YOU HATERZ HATIN ON SCREWDRIVERZ? etc)

Yet in the world of teaching, this concept is apparently inconceivable to many. I know this because the last twenty or so years in education have seen tighter and tighter screws turned on exactly how we teach and how we should be measured. It's a topic I return to like day follows night- the idea that there is a centrally prescribed 'best' way to teach, and that teachers must follow these methods or be sacrificed on the altar of Cerunnos, the Horned One. These methods, usually generated in the minds of theorists and speculative educational scientists/ homoeopaths become best practise, and we, the teaching community, brace ourselves for another drenching in slurry. Wellies on, umbrellas UP, everyone.

But I have never found teaching to be like this. While I instinctively reject any reference to tool kits and workshops that don't involve Castrol GTX and circular saws, I do like the analogy of teaching strategies as being like tools in a box; the hammer hammers, the spirit levels, the screw drives, the crow bars etc (that might not have worked. Keep writing, they might not notice). The point is that one uses what is required at the time, in that peculiar, particular circumstance. This proposition I hold to be self-evident. It leads to the following consequences:

1. My methods might not work for you

This sounds like career suicide for a man who devotes 1/3 of his waking hours to being an educational rentagob, but, with important provisos that I will detail later, it is true. My teaching style suits me; and because I am not entirely shit at my job, I know what works with my classes. I know what works for me, with my classes. Example: when I first started to not drown in classes, I realised that one of my most effective strategies with tough classes was to tell them stories. Worked a charm, and helped me build up relationships. Now that is not a strategy I advise to everyone, because not everyone can tell stories, nor could I do what they can.

We play to our skills, and to what works in the specific chemistry of the moment, of the relationship you have with your class. Remember 'Clear off scumbags' from Educating Essex? Course you do. Would you recommend that as a coda to every lesson in the UK? Of course you wouldn't. Was it appropriate for him at that time? Of course it was. That was the point the Daily Hate and others missed. He knew what he was doing.

There are some kids you'll teach who respect nothing but strength, who will punish you for any drop of kindness; there are other kids whom, offered an abstract hankie of concern, will drop and give you twenty. You learn which approach to take with which kid, and you use what works. What you don't do is stick with a one-size-fits-all strategy you expect everyone to love. People aren't like that. Students, I infer, are people.

|

| And THAT'S the Gospel Truth |

So, for example, sometimes in a class the teacher will enjoy thrilling levels of trust, and can comfortably send the class out to wander the streets with clipboards and machetes. Other classes need to be set in rows and columns, given short tasks and monitored like Alcatraz. Some classes can be trusted with the keys to your Jag; others need watchtowers and snipers.

That's why I think that a large amount of the debate in education, and over education is witless and meaningless. I remember reading the NME when I was a teen, and marvelling at how vicious the letters pages would get about the relative merits of The Smiths over, say, Duran Duran. They weren't really arguing about facts, but preferences. Similarly, when I hear teachers arguing that 'their' method is better than someone else's, and that all unbelievers must perish, I despair. What many people in this situation are actually arguing is that with their kids, in their classes, with their skill sets, such-and-such a strategy works. The correspondents should listen to each other, try to work out if there is anything transferable between their experiences, and then move on, safe in the knowledge that there may be no definitive, universal panacea to every classroom, every student.

2. International comparisons may be less useful than people hope.

|

| Here come the educational consultants! |

Nobody. Knows.

I know schools where kids are allowed to come in on flexitime. Some schools let kids out at lunch. Some seal them in like a space station. Some have uniforms; some do not. Some of them are run badly, and some well. Some could do better by imitating others, and some have the balance right.

Hitting the right note at the right time is a craft and an art, for a teacher and for a school. What works at one point, with one class, with one school, might not work another day, with another cohort, in another area- or even over time. That's why teaching is hard- rewarding, but hard. There is no formula that we can all work towards; children- people- defy moronically precise classification and compartmentalisation. It's one thing that's so glorious about being human; our variability, our potential, our almost mystical levels of indeterminism. I call it free will.

What's the formula for a relationship, exact to three decimal places? Until someone can tell me that, every teacher has the right to their own methods. We are not reagents in a test tube, nor are we blocks in a Rubik's Cube. We are humans. Some of us are teachers. And teaching is not a science.

Oh Tom,

ReplyDeleteSo very very very very very very right.

You may remember that I left teaching, this topic being one of the very reasons that persuaded me to get out.

My style worked for me, but more importantly for my kids. I know that because the majority achieved well and... they loved my lessons... and they all stay in touch via facebook when they leave. The relationship was key. To many I was their dad, too many I was 'Cookie' and I wouldn't want it any other way.

In my last post I was a member of the enemy...SLT. The school was in special measures and the new Head (who had never been a Head but had spent a considerable amount of time not teaching but instead being part of a remarkable cult - National Strategies) wanted to observe all SLT to make sure they were outstanding. The lesson (of which she saw 30 mins) was graded satisfactory. During the feedback, once she said "well your starter was too long" I switched off and as she pulled my lesson apart I was instead tuned into bunny rabbits running around a meadow with soothing tunes.

The starter set up the lesson. The started was designed for the students to work in groups to create the information that was missing from their coursework (100% Business Studies). What was I supposed to do? Cut them half way through?

Thankfully I now teach my way without the constraints of idiots doing one day GCSE workshops for an independent company. The feedback consistently says "Steve's a legend".

Why? Because I tell them stories and jokes in between working them hard. Because that is my style... not suited with today's tighter and tighter screws.

Steve

Hi Steve. That's exactly what I'm getting at; the idea that one glove fits all hands is an anachronism nobody else would accept, yet we somehow do in teaching? Well, we need to start saying no.

DeleteWhat sort of situation do you teach in now?

Tom

Hi Tom, I work freelance for 20-20 Learning (http://www.20-20learning.com) who offer a range of services, I mainly do one day revision workshops in Maths and Geography - I also do some work for an enterprise company along similar lines only its all about enterprise and work skills. I also do 1 to 1 maths in a local school three times a week. With no planning (presentations are already done for me - I just adapt a little), no marking and no idiots telling me I'm doing it wrong, its very liberating. Incidentally I run my own teacher workshops/INSET on Engaging Effectively with Parents (www.engaging-effectively.com) if you know any schools who might want it. Bargain price.

DeleteBack to your excellent post, I have referred to it as the McDonaldisation of teaching.

A salutory reminder that teaching is a dynamic thing, not a tick box activity. One gets almost convinced at times.

ReplyDeleteBe convinced. What they say it is, is what it is not.

DeleteI understand where you are coming from but I don't agree with everything you have written.

ReplyDeleteWe are there as teachers to support student learning.

How will we know that our students are not just learning, but that the learning has developed over time?

Gut instinct? Feelings? "I just know"?

Developing relationships is the key but unless we have some measure, dare I say, scientific measure that our unique teaching methods are leading to student progress then we may as well just focus on being friends to our students.

Teaching IS a dynamic thing, but it is ALSO a tick box activity. We owe that to the students.

Well, we know because:

Deletea)We observe them learning; when they show greater understanding AND recall

b) Formal external examinations

c)Other experienced teachers collaborate with our findings.

I'm not suggesting teachers do anything they please. I'm suggesting that their opinion is better resourced than a non-teacher, and that there are many paths to someone learning.

There is NO 'scientific' measure of a student's progress, so there's no point in looking for one. I think Gerry may be confusing 'objective' with 'scientific': they're not the same thing.

DeleteThink about it: student A has learnt how (say) to work out a simultaneous equation; student B has learnt some of the genre conventions of a newspaper opinion piece; student C has learnt that bullying is wrong. You can check A's progress without too many problems by setting him a short test - but even then, if he has a cold that day, he may not perform as well; and since one of the marks of 'scientific' measurement is the ability to duplicate by any informed experimenter, bang goes that 'scientific' assessment. B may well have understood the features you're teaching her, but her ability to analyse and replicate will vary hugely according to her own talent, the task set and the class she's in. As for student C - when you've worked out a 'scientific' way of assessing his progress in non-bullying, you can make a fortune publishing it - or getting yourself booked for INSETs.

Teaching is an art, not a science; pupil progress, whatever OFSTED believe, cannot be measured in 20 minutes by ticking boxes.

You are a wise scholar, ma'am.

DeleteTop stuff. Thanks Tom

ReplyDeleteAlways a pleasure, Mr Learning Spy.

DeleteGreat stuff, once again.

ReplyDeleteRe International Comparisons, I spent some time in a French Primary School last year. It was similar to the English school in which I teach (and the other four English schools I which I've taught) in as much as there were children in the building, the lead adults were called teachers, there were classroom, desks and chairs and it was called a School.

Everything else was different to what Ofsted and politicians seem to expect of a school in this country. And I mean everything - no 'school ethos', no 'building a school community', no differentiation, no 'every child must make progress', no assessment of prior knowledge in lessons, no discussion of what was learned, no school inspection as we know it in England, no anything.

And yet, French school children make pretty much the same progress educationally as English children. http://www.oecd.org/document/61/0,3746,en_32252351_32235731_46567613_1_1_1_1,00.html

Now, I know that no-one holds up France as a role model - but they do, more or less, as well as we do when it comes to measurable results... Draw your own conclusions.

Thanks for the info. I DO draw conclusions from that. I conclude that our constipated anxiety about the things you describe are a fairy tale, designed to scare and soothe ourselves simultaneously.

DeleteBBCR4 Analysis,Do schools make a difference/counter factors such as social and family background?? http://ow.ly/99Z2K not much -if at all. But stay optimistic is the message.

ReplyDeleteAnother true post. Different styles and approaches is why in my school (and in lots of others I'd assume) we get the trainees working with as many different teachers as possible - we don't want them doing a poor impression of their mentor, because that's all they've ever seen. And of course you treat certain classes and kids differently to others. I think the only danger of 'career suicide' for you is that you keep posting common sense on a public website - there must be some GTC guidelines agains this, and it would count against you if you ever wanted to become a DoE adviser...

ReplyDelete@Gerry - I see what you mean, although 'scientific' is totally the wrong word for the kind of levels data we have to work with. The question is, how do you stop whatever measure(s) you use being deified as a God of Statistics, to which every other measure and consideration must bow down?

Thanks Neil. I'll keep saying what I see until they hang me for it. Then I'll say it from the rope :)

DeleteAnd the way we stop gamification of the current metric, is by refusing to nail schools and teachers for failing that singular metric. I advocate a spectrum of assessment measures for a school.

Amen TB.

ReplyDeleteNice to see your Anonymous face in these thar parts, stranger *spits* *misses spitoon* *hits GTC*

DeleteBrilliant as always Tom.

ReplyDeleteFor me the important bits in here are context and the children you teach and devising ways to help them learn.

And that means not applying tools or methods that are not suited to these particular children (the ones in front of you). Perhaps even inventing things to help them learn (innovation in learning).

I also agree that international comparisons are an excuse to make consultancies huge profits. They promise that they can read entrails They sell the belief that they are able to understand and compare. It is cargo cult thinking.

http://zhaolearning.com/2010/10/20/cargo-cult-science-mckinseys-report-on-teacher-recruitment/

I do however believe that it is reasonable to have measures that help you learn and improve. One of the measures can be the occasional test that you have designed, to help you understand how well your children have learnt and understood. Used locally, and not turned into a huge exercise in competition and league tables.

I also believe that it is not unreasonable that your school uses measures to learn and understand. But your measures could be different from others school's measures. Some you might be temporary and others permanent.

These will give you greater depth and insight into how well your methods work.

But these are your measures and not some huge labyrinthine Ofsted compliance regime. Nor are they messages that many of those selling text books or standardized exams would support.

Great, thought provoking response, thanks Howard. And thanks for the link to Yong Zhao, someone I haven't come across. Anyone who reads Feynmann is a friend of mine :)

ReplyDeleteTom

Dear Mr. Bennett,

ReplyDeleteI work for Bloggingbooks which is the new publishing brand of SVH publishing house (svh-verlag.de).

We are expanding our publishing programme and we have just started in publishing blog posts.

In this respect, we are glad to offer you the possibility of publishing your blog posts as a book.

Should you have interests in the publication of your posts or should you have any question, I would be pleased to answer your queries by e-mail.

You will find more information about our publishing house on our website: bloggingbooks.de

Looking forward to hearing from you

Best regards,

contact e-mail: m.gorbulea@bloggingbooks.de

AND YET I was still told to submit lesson plans showing progress in 20 minute chunks. Resistance was futile.

ReplyDeleteResistance is never futile. At least you won't have been assimilated...:)

DeleteThanks again Tom for putting into words what so many of us 'old timers' know in our hearts, but can't always manage to articulate (without starting sentences with 'Back in the old days before Ofsted and league tables .......').

ReplyDeleteAfter years working in what once were good state comprehensives, and four years as a PGCE course external examiner, I just had to get out of the system and since then I've worked in private schools, most of which (interestingly?) don't fully subscribe to 'state-standardised' approaches. I meet so many younger teachers who are being brainwashed by the constant barrage of cloned teaching techniques that I fear for the future of genuine educational innovations and teacher-pupil/student (note: pupil/student - not 'learner')relationships.

Keep fighting the good fight Tom!

Bill

As long as there is breath in my body, Sir :)

DeleteAs someone who was trained in the years of the Primary Strategies, I'm beginning to notice how narrow teaching strategies have become. I've only ever taught and observed others teaching using 'traditional' methods - a three/five part lesson, mainly instruction, independent work, plenary.

ReplyDeleteOver my 7 years in schools I have tried out different ideas I have come across (mainly on teaching forums and certainly not through any school CPD) and had some brilliant creative lessons - but none of these would have been even satisfactory in Ofsted's opinion, as I probably didn't share objectives or measure children's learning against them. However, the 'different' lessons were by far the most inspiring for me and for the children and led to real motivation.

For example, we had a workshop about dinosaurs and I needed to teach about perimeter. So I took the class out on the playground and told them that we needed to build a dinosaur enclosure the size of the netball court, and they needed to work out how much fence to order. I gave them no success criteria and the task wasn't differentiated, I just set them off. They began by using non-standard measures (their own feet mainly), then some started to ask for metre sticks and trundle wheels. I intervened and questioned to move them on. They used whiteboard pens on a large whiteboard for calculations. Result: Some fantastic work on finding the perimeter of the netball court, really enthusiastic learners, some really high level calculations, and me knowing what misconceptions to address in the following lesson. That lesson was a more 'traditional' chalk and talk style lesson because I needed to teach them the things they obviously hadn't quite understood. Great lesson for all involved.

However, I doubt Ofsted would be impressed, and I doubt I will ever know for sure, because I wouldn't dare do a lesson like that for an observation, due to the fear of it all going wrong and not being able to show that all children made good progress. The only way to do that that I can see is to stick with the ordinary and structured, which is a great shame.

So thanks Tom for pointing out that one teaching style doesn't fit all.