This engine runs on hope: why schools need to defy the destiny of data

Chris Cook has written an excellent sidebar to Fraser Nelson's enthusiastic love letter to the Swedish model (and if that doesn't make you wave a pretend cigar and wag your eyebrows like Groucho, then there is no hope for you). It's a cautionary note to the symphony of success that the Swedish Free School system, running parallel to the state sector, seems to exemplify. In summary, he advises that its benefits, while statistically significant, aren't exactly enormous. At the heart of this, and in other good pieces he's written, he describes how a huge part of a child's success is down to where they're from, not where they're at.

Its a topic I often think about: what does it matter what we do? As Christopher rightly says, aren't the historical and economic narratives of the children's background the real levers of destiny? And in many senses they are, of course. But to be a teacher, it's vital that we....almost ignore this. I wrote about it here:

'In life, we often get what we expect, not what we

deserve. We create cages within our own minds, and say that the horizon

is as high as we lift our eyes. How many children sit in a school where

the targets on their books say G, F or E? How many schools are judged

by the damnable, damned engines of purported certainty that the Hellish

FFT data suggests? How many teachers look at a kid and expects nothing

from them? How many parents? How many schools? I set all my pupils two

targets: one given them by the desiccated, blasted data that precedes

them, and one of my own, which is far more important. And I let them

know it.

Rarely do I set anything other than an A.

Why? Because I bloody well expect it. I don’t care how poor a kid is,

and I certainly don’t give a damn what some hypothetical bell curve says

a kid is capable of. If they have a sound mind in the most general

sense, I tell them where they’re aiming- an A. I know how to do it. I

know how they can do it. If we don’t get there, then I don’t waste a

tear on it if everyone tried their best, including me. Especially me,

sometimes.

I despair of our contemporary insistence

that children submit to market models of tagets, when they are human

beings; that teachers kneel before the tyrant of the perfectly elastic,

infinitely expanding mad universe of the stockbroker. I’m not a middle

manager in a branch of Comet. I’m a Teacher.

Until we have a system that demands- and

expects- all students to try their best and do well, rather than

concedes that they can’t, and so the bars must be set lower and lower

until they bury themselves in the ground, then we will get exactly the

children we deserve. You want social mobility? You want an end to

generational narratives of endless, empty poverty?

Expect more.'

And I returned to it, like a nervous murderer, in this blog, and I quote:

'So when the FFT says that a given child is estimated a B at GCSE, based

on prior attainment data, once social and circumstantial factors have

been accounted for, what does it mean?

Almost nothing. Almost nothing.

What it means is that many children with similar socio-economic and attainment levels achieved that grade. So what? Most children in Mozart's street didn't grow up to write The Magic Flute, but he did. Most children from Omaha, Nebraska didn't grow up to lead a black consciousness movement, but Malcolm X did. I taught a kid who scraped a C in bottom set RS, who scored a U in AS, and then an A at A2. The human spirit is a genie; it is absurd, noetic, a screaming eagle of ambition and indeterminacy. It is a ghost, a comet, a nuclear furnace of optimism and ambition and impossibility. It is also a disappointment; the anti-life, failure snatched from the jaws of victory. House prices can go up as well as down. That is what makes being alive so glorious and terrifying.

I have a knowledge of my children's predicted grades that approaches telepathy, because I know my subject and I know my kids. But every year I am knocked sideways by kids who exceed my expectations and those who ridicule them. Nobody can predict the future. Guesses are fine, but let's admit that's what they are.

Guesses.

Let's stop pulverising children with our bureaucratic assumptions about their potential. Can you imagine what it must feel like to be told by your teacher that your prediction is a D?

F*ck. That.

You know what my expectation of my children is? An A. For everyone. That's the target I set myself, and if I don't get it, well, I try again next year. I don't cry into my coffee, I just try again.

Here's a thing: what does it even mean to 'aim for a C, or a B'? Have you ever seen a kid revise, and try to get a B? It's nonsense. Kids try as hard as they can/ can be bothered, to get the best grade they can. If you set a child to run 100 metres, and they really bash their guts out on it, can you imagine asking them, 'What speed were you going for?' No. They just run. They just run. Target setting has become the fetish of 21st century teaching. It is another ravenous, ridiculous imported imaginary animal from the paradigm of the market place, where ambitions are plucked from the air- and they are- and called 'predictions', when they should be called 'hopes'.'

Almost nothing. Almost nothing.

What it means is that many children with similar socio-economic and attainment levels achieved that grade. So what? Most children in Mozart's street didn't grow up to write The Magic Flute, but he did. Most children from Omaha, Nebraska didn't grow up to lead a black consciousness movement, but Malcolm X did. I taught a kid who scraped a C in bottom set RS, who scored a U in AS, and then an A at A2. The human spirit is a genie; it is absurd, noetic, a screaming eagle of ambition and indeterminacy. It is a ghost, a comet, a nuclear furnace of optimism and ambition and impossibility. It is also a disappointment; the anti-life, failure snatched from the jaws of victory. House prices can go up as well as down. That is what makes being alive so glorious and terrifying.

I have a knowledge of my children's predicted grades that approaches telepathy, because I know my subject and I know my kids. But every year I am knocked sideways by kids who exceed my expectations and those who ridicule them. Nobody can predict the future. Guesses are fine, but let's admit that's what they are.

Guesses.

Let's stop pulverising children with our bureaucratic assumptions about their potential. Can you imagine what it must feel like to be told by your teacher that your prediction is a D?

F*ck. That.

You know what my expectation of my children is? An A. For everyone. That's the target I set myself, and if I don't get it, well, I try again next year. I don't cry into my coffee, I just try again.

Here's a thing: what does it even mean to 'aim for a C, or a B'? Have you ever seen a kid revise, and try to get a B? It's nonsense. Kids try as hard as they can/ can be bothered, to get the best grade they can. If you set a child to run 100 metres, and they really bash their guts out on it, can you imagine asking them, 'What speed were you going for?' No. They just run. They just run. Target setting has become the fetish of 21st century teaching. It is another ravenous, ridiculous imported imaginary animal from the paradigm of the market place, where ambitions are plucked from the air- and they are- and called 'predictions', when they should be called 'hopes'.'

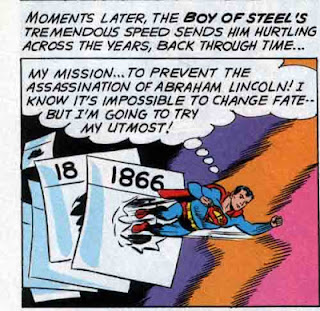

I can't fix the world. I can't smash the time barrier with my bare hands and save Abraham Lincoln. But I'll cease to exist before I stop trying to show every child in my room that they can rewrite the book of their own lives.

That's great. It reminds me of some support I was doing a school quite a while ago on a revision day for Y11. A boy came into the class with his target grade slip. It said What did I achieve in the mock exam: D/ What is your target grade: E/ What do you need to do to achieve this? We both agreed that he needed to work a little less hard. Nonsense. Too much pressure from above to constantly be banging about targets, when we should just be expecting the absolute best from everyone. Grrr.....

ReplyDeleteHa :) Good example

DeleteIt's a nice idea. Sweetly life-affirming and positive. Any reservations will be met with the "So you don't WANT children to achieve???"

ReplyDeleteTbh, the fetishisation of data and targets remind me a lot more of Soviet practice than market theory. I used to be a specialist in the study of failed Soviet states, North Korea in particular. When I became a school governor, I soon found that EXACTLY THE SAME mindset is required at state schools for management of kids attainment. There is no place in this mindset for kids who don't fit the dessicated learning unit model. I didn't stay a school governor for long, and this personal anecdote explains why...

ReplyDeleteMy eldest kid is deaf. Very, very good non-verbal reasoning; very, very delayed language, which has limited his attainment. Despite the difficulties he has, he loved learning; lived for it, if truth be told. This was partly down to what we did as parents, mostly down to his teachers' approach and expectations. That love for learning was strangled a few years ago.

ReplyDeleteTwo things happened: Firstly, the school received a notice to improve from Ofsted. Its crime? Insufficient data collection and non-approved methods to track progress. The head was defenestrated a week later, and a consultant head was appointed by the LA to get the school out of category.

The second thing that happened (a few weeks later) was that my eldest's cochlear implant failed. The cochlear implant provided him with 95% of his useable hearing. He was re-implanted quickly, but he needed a specialised programme of rehabilitation so that he could make use of the new one - think Luke Skywalker's robot hand in the Star Wars films. Usually, it's about a six-month process. It's very, very difficult to make this rehab programme work properly without teaching staff, NHS staff and parents working together.

Under the old regime, the school would simply have altered the targets it had for the child to prioritise this rehab programme - after all, it's kind of hard to make good progress in literacy and language when your main source of both has gone. But that was the old regime. The new regime had different ideas.

The teacher had changed the targets for my kid - lower attainment expected in literacy until rehab had been completed, rehab the priority. No change to numeracy target (bright non-verbal, remember?) The new consultant-led SLT summoned the teacher to a meeting. At this meeting, it was explained that only two sub-levels of progress were allowed under the new regime. No excuses would be tolerated, as Ofsted would place the school in special measures if the data did not conform.

The teacher - inspirational, effective, a credit to the profession - was given a stark choice: restore the two sub-level literacy target for my kid, or find her future at the school gone. The teacher chose the former. We kept the rehab programme going at home and with the NHS staff; the teacher though was forced to teach my kid to a programme that assumed nothing had happened to him in the last few months. I complained to the the governing body - sympathy was expressed, but they backed SLT - nothing was allowed to derail the process of getting the school out of category....

2/2

ReplyDeleteThe end result? He got his two sub-levels. The school came out of Ofsted category. But all this came at a cost. The rehab programme took longer than it otherwise would have done. For the rest of that year, he had a curriculum that he could barely access, delivered and distorted with one aim, and one aim only: to get his data to conform. There are holes in his understanding that we are still patching today.

The biggest casualty of all was his intrinsic and deep-rooted passion for learning about the world. He now thinks of learning only in the context of something that can be measured and quantified; he is obsessed with learning that can be demonstrated, that translates into level attainments. He works like a harnessed pair of Trojans, but there's no love for it any more. It's indescribably sad.

It's also indescribably sad to see teaching professionals who I respect and admire treated in this way. I don't blame the teacher at all. It's the Stalinist data-driven cult - and the uncritical devotees, cynical exploiters and useful idiots that keep it going - that must die.

Tom, thanks for putting this article out. Our kids lives aren't predestined. My eldest is still some way behind his peers - but with the right help and approach, he will get to achieve his potential. But I firmly believe that the only way he can do this is if his teachers are given the chance to reject the FFT nav-computer, and switch to manual. It does my heart glad to hear that people in the profession still feel this way.

Hi Beefo

DeleteSorry to take so long to get to this. That's a powerful story, and resonates with my experiences as a teacher. Thanks very much for posting that, and I wish you and your son all the best in the future. I believe- and hope- that anyone who loves learning from an early age can never really have it knocked out of them. Competitiveness is fine, especially when it's with oneself, but it never killed anyone to try to be the best in their peer group. Maybe that's what occupies him.

All the best

Tom

Reminded me of a great day in Boston hearing Benjamin Zander talk about his teaching strategy. All students can be A students. Then found a similar talk on YouTube taken at NCSL ... http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTKEBygQic0

ReplyDeleteThanks Tony

DeleteYes, but all students can't be A students - at least, not when innate ability counts for anything. I could never run the hundred yards in less than 20 seconds, how much I tried. In my own subject (English Language A-level) students who work ferociously hard can achieve excellent grades in the exam, because it's mainly learning and practice; but they can't all get As in their coursework, because that's only partly learnt techniques, more verbal ability and manipulation of language.

ReplyDeleteHaving said that, I do agree with the ghastliness of target-led teaching.

Well, they probably can't all be A students (especially when it's norm-referenced) but that applies to a cohort. When I look at an individual, the probabilities start to widen. I've seen some spectacular successes that show me incredible achievement is unlikely in the most unlikely of places. Of course, that doesn't mean that anything is possible. It is unlikely the Folies Bergere will be looking for my happy feet any time soon. But we need to do away with the 'You can't' mentality, especially when it is married to predicted grades that are less scientific than homoeopathy.

DeleteCheers

Tom

Applying any kind of target grade to an individual student is questionable not only for the reasons Tom has flagged up here, but it is also statistically misleading. Using these target grades is a statistically valid way of looking at how a cohort has performed against some kind of standard measure, but it is pretty misleading and inaccurate for individual students. The target grade will be based upon how on a distribution of students with similar entry grades/measures. As such it will either be the most likely grade or if benchmarked in an 'aspirational' way a bit above this. As such it is more likely for the student to NOT get that grade (get one of the other grades). It is also the case that many students will get grades lower and some higher and this is actually to be expected. Obviously with a large enough sample this balances out, but for an individual student it is pretty pointless.

ReplyDeleteTRUE. DAT.

DeleteThere is a little known, but directly causal ink between the IT industry and the fad for data driven reform in schools. Not a few major figures in the IT industry, whose work brought them into contact with education, found it baffling that the faith they placed in data as IT engineers, wasn't replicated by schools.

ReplyDeleteAnd there is also a cultural aspect to this. Ask a US teacher how any child in their classroom is doing, and they will almost certainly press a button on a printer and hand you a sheet of stats before saying, "That's how they're doing." Ask any half decent teacher in the UK the same question and you will get a credible, detailed description of a real child.

The 'must progress by two sub-levels per annum' mantra expoused by many primary schools is the most (tragi)comic, particularly when progress is assessed by the very same teacher who is awaiting judgement on whether or not such a jump takes place. Fun times. It also seems completely at odds with the apparent shift towards a proportial 'only the top 10% percent can have an A grade' culture which seems to be creeping in at GCSE level via the Ofqual/AQA fiasco. How will that work if the number of A grade FFTs exceeds the quota?

ReplyDeleteAttain, attain, attain! But not too much lest we should give the impression that exams are getting easier... I do love the clarity of our lords and masters.

Has anyone actually looked at the FFT website or read up on how their data is collected? FFT actually tell teachers that their data should not be the only source of information with which to set targets and should be used for predictions. Instead it seems teachers everywhere are told that FFT data ARE predictions. I spoke with one of my deputy heads recently who explained how we get our FFTD targets. He showed me a spreadsheet full of data. They just choose the grade which is most likely achievable. But they are also as likely to achieve a grade lower or higher. What goes on in a student's life is never taken into account. They cease to be seen as hunmans but become a set of figures.

ReplyDeleteBrian, the FFT was the brainchild of Mike Fischer, one of the original founders of RM (I've no doubt it was kindly intended) but its origin and current use, exemplifies my earlier point.

DeleteI just found your blog today-I read one of your newspaper articles and I wanted to read more. You are quite inspirational. I will definitely keep up to date with this blog. I want to be a teacher, and there is some really good reading here to keep me thinking. Thank you!

ReplyDelete