Would you like a tissue for that? Why teachers make terrible therapists

From the second I stepped into

classes, I started to drown in the issues that running a room with multiple

students entails. Children who come into school with clothes unwashed between

weeks; hungry kids; latchkey kids; kids enduring abuse, domestic humiliation,

poverty and anxieties of every conceivable shade. Unless you are very

fortunate, or very callous, you cannot have failed to notice this. Even in the

most fragrant arbours, where every physical need is met there are camouflaged

pockets of deprivation in other areas: neglect, abandonment, cruelty.

And it struck me, equally

instantly, that classrooms are terrible places in which to do anything about

this. Yet we are tacitly expected to. One of the problems of philosophical

models of humanity is that it often assumes that people are perfectly rational,

when they are clearly not; similarly, many school structures are constructed on

the understanding that children are neutral recipients in the classroom

experience, when they are reagents. Children are like Jacob Marley, dragging

the chains of their entire lives with them.

It is essential for the teacher

to lay clear boundaries, to police those boundaries, and to reward and sanction

as consequence demands. These foundations are the womb of structure, creating a

safe space where everyone is valued equally, where children know where they

stand, and where they know what they have to do next. Without structure, law

and consequence there can be no justice, no education. That's absolutely

fundamental to the efficient execution of learning in an institution.

But what about the ones who have

problems that cannot be amended by clear boundaries and consequences? There are

children tortured by anxieties and social dilemmas so enormous that it is

almost impossible for them to comply in a meaningful way. This can range from

autism to Tourette's, to the knowledge that their father will be ready with a

belt when they get home, because it's payday and he's drunk. What then?

And this is where the dislocation

occurs. Every school has children that need extra help. But the place where

this is often expected to occur is within the classroom. Take a humanities

teacher in the average secondary school. He might stand in front of 300

different faces every week, many of whom might be seen once only. There will

certainly be about 25 children in every room. Even if he divided up his time

equally between them, they would be lucky to have two minutes apiece, and that

would mean no teaching at all.

Who can stop the Juggernaut?

And teaching has to be done. It's

our primary role. It's how we're held accountable. The juggernaut of our jobs doesn’t

slow down because one passenger has taken ill; try to do that too often, let

the bus go under 50, and the bomb goes off. So children, whom with support

could be turned around, are instead crushed under the wheels of the truck.

|

| 'Of COURSE I have time. Nothing but.' |

And I'm not criticising the

truck. I’m driving the damn truck. Teachers don't have the ability, the time or

the resources to run personal mentoring sessions with every child. If we did,

we would never leave school, and neither would they. Unfortunately, the very

best thing, the most efficient thing that can be done in instances of, for

example, bad behaviour, is the administration of clear boundaries and the

consequences attached to them. As a strategy, it has the benefit of utility for

the majority of children, whose behaviour is amenable to direction, and who

have the inner resources to respond to the prod and the goad of punishment and

reward. But the minority: the very broken, the fractured, the abused, the

vicious, the totally lost, frequently fail to respond. The process must

continue, otherwise we ruin the structure that keeps most of us healthy and

whole, but the imperfection is obvious.

The problem is partly resources.

A child who is paralysed with anxiety about looking stupid in lessons might

curl up like a hedgehog in the classroom. A good teacher will be able to spot

the difference between shades of refusal, but apart from a few carefully chosen

words in or after the lesson, and a short chat with home, that's as much time

as we have before we need to deal with a hundred other issues. To help that

pupil through their non-compliance is the work of several weeks of coaching,

coaxing, probing and mentoring.

Or the problem might be worse,

and it's a kid with ten years of mucking about under their belt because of a

million other reasons; yet we have to tend to them too, and hope that we can

unpick the million stitches of their lives and accrued character and somehow

teach them about German verbs or trigonometry. Sisyphus would pity us.

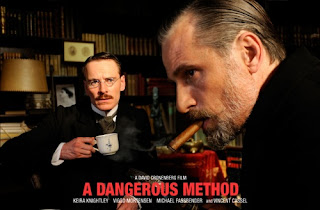

A Dangerous Method

The point of well-run behaviour

management isn't just to identify those who should be praised and punished;

it's also to identify behaviour problems and then refer them to ways in which

these behaviours can be amended. And that's when the system breaks down,

because we simply don't- in the majority of cases- have the time. Nor the

training. Do you know how to deal with an anorexic pupil? A pupil shuttled

between homes all her life? A pupil who believes she's evil and worthless?

We were asked and trained to

teach. We were hired for our subject expertise and perhaps a classroom skill.

But we are required to be therapists, and we simply aren't. The classroom is

the very worst place for that sort of help. Good mentoring and coaching is done

in small groups, probably one-to-one. The adults who are good at this usually

aren't teachers. And teachers are often very poor mentors, not through deficit

of will, but of opportunity.

I spoke at a conference about

mental health this week; the audience were mostly therapists, child

psychologists and the like. And I was fascinated by the abyss that existed

between their role and mine. My job is to run a room and teach my subject.

Theirs is to mentor and heal. If you've ever been given an Ed Psych report on

'teaching styles suitable for pupil x' and looked at it with scorn, you'll know

what I mean. It's easy to say 'child x should be allowed to run around the room

when he is anxious' or 'let him leave the room whenever he wants' but it is the

very devil to run a room that way, when the other children, quite rightly,

wonder why they can't enjoy the privileges of the statements party.

And I can understand a child

therapist rubbing their brow in despair when I talk about the need for fairly

rigid classroom structures, where pupils have to be taught that their actions

will have consequences, pleasant or not. My tactics are blunt, and designed to

appeal to the majority. But I work with a best-fit model. the therapist usually

doesn't teach classes, and his little

idea how one-to-one relationships become scaled up to the level of a class.

Schools on the Couch

The schools best at this are ones

that make mentoring a backbone of their strategy; where the internal exclusion

unit is run by trained professionals who have experience in both child

behavioural issues as well as subject knowledge. Where children who deserve

punishments are discerned from children who need assistance. Where exclusion

from the classroom is as much about a genuine effort to identify and deal with

problems rather than simply a short spell in the cooler. If teacher's

timetables were reduced, this would be a huge step, because then they would

have time, not merely to plan and assess, but also to consider these issues. Or

perhaps better still, the role of the tutor, or Head of House could be made

muscular, and given the time and training they need to focus on these matters.

As it stands, the two groups need

to understand each other more. Teachers aren't therapists. Therapists aren't

teachers. When we pretend they are, everyone’s a loser.

This echoes my feelings of frustrations with how to help students that are poorly behaved across the school. Detentions, phone calls are all fairly pointless. They need help and there's nothing I can do to resolve or even lighten the load of the issues that are no doubt at the root of their poor behaviour. @optotoxical

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely agree with this. and the attitude of management can make a huge difference_do they encourage a teaching majority led approach or a very individualised one which really only suits the minority of one or two

ReplyDeleteCouldn't agree less. Teachers don't need to be therapists but do need to be aware of vast range of needs and have some idea of where to go for additional support if they are beyond your personal capability/ experience. Have seen schools/ individual teachers as havens of calm and safety for children with dangerous and chaotic lives and seen uncaring/ bullying teachers do irreparable damage.Early intervention and working with parents vital can see why secondary teachers in difficult circumstances can become cynical. Agree many schools under resourced but also true that many lack flexibility and imagination to do any better than train to conform. Not what it's all about for me. Every Child Matters not just a trite soundbite for me.

ReplyDeleteI agree and disagree. You were never that pupil were you? All of that discipline stuff that you write about, it works as long as you're not the pupil who's going f***ing mental inside. In the same way, you are expected to teach a class and your focus is the lesson, greater good etc, those kids are expected to sit through those lessons and learn which is equally as challenging to them as their behaviour is to you. Only you get to be the boss in this situation and control the environment; they are at your mercy. Which makes you either a god or a b*****d.

ReplyDeleteRe: All of that discipline stuff that you write about, it works as long as you're not the pupil who's going f***ing mental inside.

ReplyDeleteAnd all that "law stuff" that you will be expected to follow as an adult works as well, even if you are going mental inside.

The police will work to arrest you

The judge will work to sentence

And the jailer will work to make sure you don't escape

Better to learn that reality in Tom's classroom than in a jail cell I say